Republican Mayor Erin Stewart’s budget for the upcoming year once again flat-funds city operating funds for New Britain schools.

Stewart has been criticized for repeatedly flat-funding the city’s funding for the operating budget of New Britain schools. As expected, she froze annual operating funds for New Britain schools in her budget for the city budget year that starts on July 1, 2021 and goes to June 30, 2022 – often called fiscal year 2022 or FY2022.

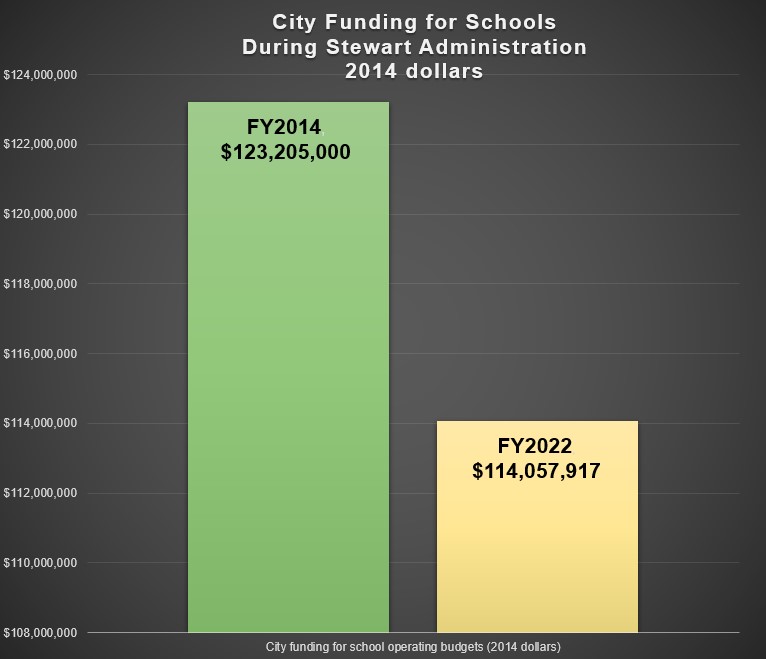

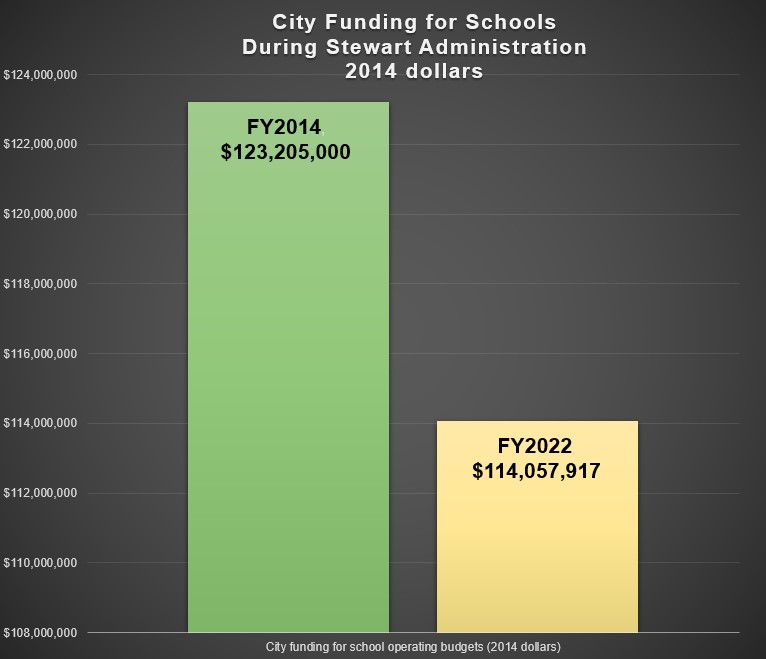

But as Stewart comes toward the end of her eighth year in office, the impact of her repeated freezing of city support for education has a magnifying impact, as inflation has overwhelmed what little increases Stewart has allocated in operating funds to the city’s schools.

In current year dollars, Stewart has added what amounts to six tenths of a percent per year to the city’s support for operating New Britain schools, going from $123,205,000 in FY2014 to $129,014,835 in her newly announce FY2022 budget. Most of that increase, however, is actually in the form of about $3.3 million in state special education grant funding that is now transferred to the school system. The actual allocation from the city to the schools remains $125,700,000.

But, that 0.6% annualized education increase per year has been, by far, overwhelmed by inflation over Stewart’s eight years in office, raising prices by more than more than 13% over that time.

That means that the net result of Stewart’s budgeting been a cut in real dollars to the city’s funding for its schools. That education cut under Stewart appears to add up to a whopping $9 million per year.

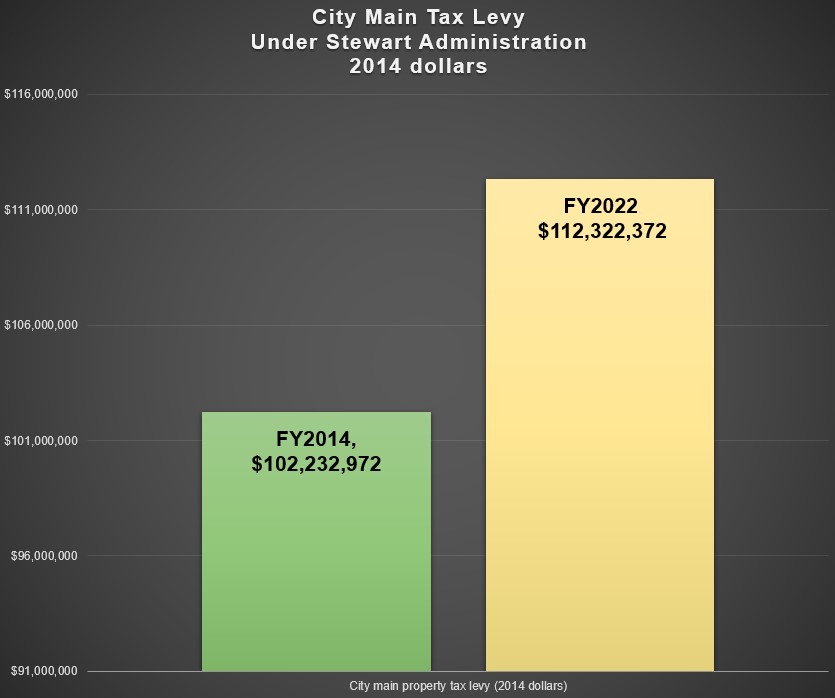

Yet taxes in that same period have been increasing substantially. In current year dollars, Stewart’s budgets have increased the city’s regular tax levy by 24% over her eight years as mayor – almost $25 million more in taxes. Even in 2014 dollars, Stewart’s budgets appear to collect 10% more in taxes than when she first started as mayor.

Impact of Low City Schools Funding on Low School Test Scores

Stewart has come under intense criticism in New Britain for comments she made in her annual “state of the city” address this year, in which she doubled-down on her underfunding of the city’s schools. Stewart bluntly said that her longstanding policy of low-funding to New Britain’s schools would continue in the city budget for the upcoming year, saying, “what I will not do is blindly throw additional tax dollars into a massive bureaucracy that is failing our students.”

City leaders strongly criticized Stewart for those comments, and for her low funding for New Britain schools, in general.

Stewart essentially admitted, in her state of the city comments, that she has flat-funded the city’s schools, saying, “Every year, the Consolidated School District of New Britain receives about $126 million of taxpayer money, and today, it is dead last, when every metric within the state of Connecticut education performance index.”

But critics have pointed to Stewart’s flat-funding of schools as an important reason for those low academic scores.

The New Britain Progressive reported in 2019 that, despite New Britain receiving, “the fifth highest state Education Cost Sharing grant funding of all of the cities and towns in the state,”

New Britain’s own local commitment to education, on the other hand, is among the lowest municipal school districts in the state. Only Bridgeport allocated less local funding per student than New Britain in the 2015-2016 state data.

While New Britain residents have less money than the state average to fund local services, the New Britain Progressive reported that, even looking at a percent of the city’s ability to pay, the city of New Britain still appeared to allocate to its schools, “the second lowest among municipal school districts in the state.”

Hartford’s contribution was not in that data and may have been lower, still, which would have made New Britain third lowest.

The New Britain Progressive also reported in 2019 that,

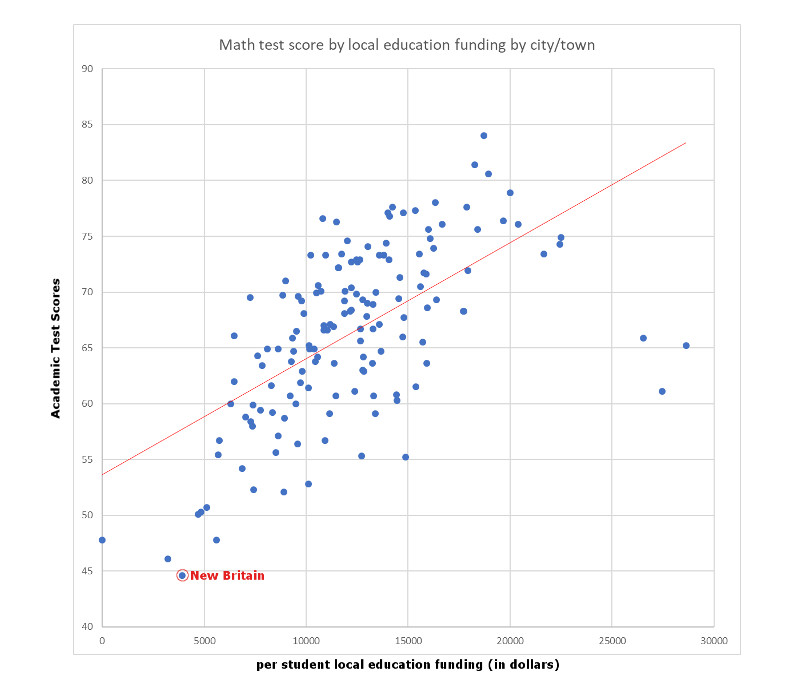

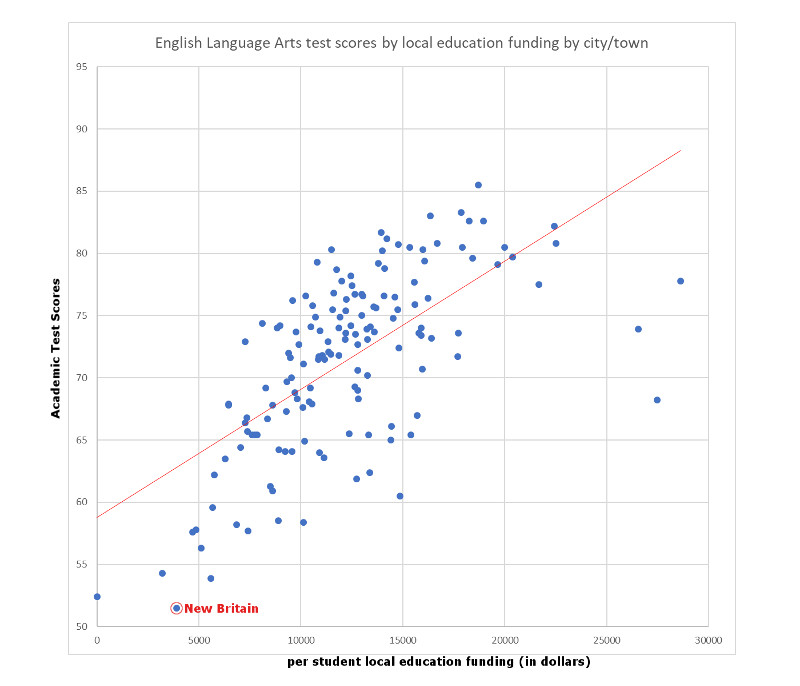

Comparing the amount of local support for education, using the 2015-2016 data, to the most recent academic test scores appears to show a general correlation between how much a city or town provides in local funding for their schools and the test scores of the students in their schools. The comparison appears to show New Britain’s place near the bottom of both local education funding and test scores as part of a larger pattern, with New Britain near the low end of the scale.

In 2019, the New Britain Progressive reported that, at that time, it appeared that it would have taken a $14 million or more per year local education funding increase from the city to get the city up to the average amount cities and towns spent as a portion of their local ability to pay, apparently leaving New Britain’s city commitment to annual school operating budgets far behind the benchmarks that appear correlated with higher educational outcomes.

Many have accused Stewart of obfuscating the city’s responsibility for supporting the education of New Britain’s kid, with some speculating that Stewart does not consider it the responsibility of the city at all.

The city’s schools have relied heavily during Stewart’s administration on increases in state aid brought into the city by the governor and the city’s state legislative delegation. The current two year state budget increases state Educational Cost Sharing Grant funding for New Britain schools by $8,146,298, according to the nonpartisan legislative Office of Fiscal Analysis. Senator Rick Lopes (D-6), then a state representative, Rep. Bobby Sanchez (D-25) and Rep. Peter Tercyak (D-26) voted to approve that budget. Rep. Manny Sanchez (D-24) was elected to the state legislature later that year.

“We have delivered millions back to our city,” Rep. Bobby Sanchez has said, “but without partners on the city level that care about education our schools will continue to be underfunded.”

Taxes and Debt

Facing strong opposition in this year’s city elections, with three Democrats waging or weighing a campaign against her, Stewart has proposed reducing the mill rate from 50.50 to 49.50, apparently paid for with federal and state aid – and a $12 million reduction in the city’s debt service.

Stewart has come under intense criticism in the past for having repeatedly borrowed money to push millions of dollars of debt into the future to artificially lower costs during her administration at the expense of higher future debt payments for city taxpayers.

Stewart was heavily criticized, as well, after the 2017 City elections, for strong-arm tactics to pressure the, then, newly-elected Democratic majority City Council to approve $115 million in additional borrowing to pay for an anticipated increase in annual debt payments that would have occurred over the following few years.

Critics pointed to the spike in annual debt payments Stewart sought to address with increased taxpayer borrowing as having been caused by past borrowing Stewart had employed to balance the city budgets without increasing taxes more than she already had or by cutting spending.

Criticism of Stewart’s budget practices have focused on increases in City Hall spending, while she largely flat funded annual operating funding for the city’s schools.

In 2020, yet another $70 million debt refinancing plan was criticized for apparently adding $30 million to taxpayer debt. During consideration of that plan in 2020, the city’s debt underwriter, John Healey, noted that the borrowing and debt refinance plan would reduce city annual budget costs by $19 million in fiscal year 2022, and that, without that, the city could be facing a budget deficit of $14.77 million for that budget year.

During consideration of the 2020 debt plan, Healey had also noted that, even after approving that $70 million borrowing proposal, it would be likely that the city would likely “need” to “restructure” its debt, again, in another three and a half years.

A committee in the Republican-controlled City Council had been set to meet, on the same day that Stewart was to present her annual budget, to consider an additional $7 million in debt refinancing, but that meeting was suddenly cancelled after it was reported in the New Britain Progressive.

Editor’s note (4/20/2022): The article was updated to reflect that the total amount of city education funding, counting the state special education grant funding, and the amount of that state grant were adjusted to reflect a change in the methodology used to calculate these figures.